I had originally switched to Blogger because I couldn't use Google AdSense on WordPress but... looks like Google has frozen my account without explanation so... Back to WP for me!

Thank you for your interest in my art and thoughts on Black culture. Please come find me on WordPress and subscribe via email. :-)

Tuesday, August 18, 2015

Saturday, April 18, 2015

Saturday, April 11, 2015

Sketchbook Saturday

This is a charcoal sketch I did in 1992. I still love working with charcoal because I like to smudge it for a smooth texture. I used to do my hair like this a lot so it may actually be a self portrait (kind of). It was also how Janet Jackson did her hair in the Pleasure Principle video so maybe I was trying to draw her. Not sure now!

Saturday, April 4, 2015

Sketchbook Saturday

This week is a four-in-one! I don't know exactly when these are from since they are just labled 1990s in the file. I had kept my hair shoulder length or longer when I was in my teens but was considering chopping it all off into some cute short cut. The drawings below are of some ideas I had of what I wanted to maybe do. The first two I think were what I thought one cut would look either curly or hot ironed. Notice the rat tail on the third one! I changed my mind and kept it long because I just loved my hair too much!

Wednesday, April 1, 2015

National Poetry Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - William Stanley Braithwaite

|

| Poet, William Stanley Braithwaite |

~~~

From Wikipedia:

William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite (December 6, 1878 – June 8, 1962) was an American writer, poet and literary critic.

Braithwaite was born in Boston, Massachusetts. At the age of 12, upon the death of his father, Braithwaite was forced to quit school to support his family. When he was aged 15 he was apprenticed to a typesetter for the Boston publisher, Ginn & Co., where he discovered an affinity for lyric poetry and began to write his own poems.

From 1906 to 1931 he contributed to The Boston Evening Transcript, eventually becoming its literary editor. He also wrote articles, reviews and poetry for many other periodicals and journals, including the Atlantic Monthly, the New York Times, and the The New Republic.

In 1918 he was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In 1935, Braithwaite assumed a professorship of creative literature at Atlanta University. He retired from Atlanta University in 1945.

In 1946, he and his wife Emma Kelly, along with their seven children, moved to Sugar Hill—a neighborhood in Harlem, New York—where Braithwaite continued to write and publish poetry, essays and anthologies. He died at his 409 Edgecombe Avenue home in Harlem after a brief illness on 8 June 1962.

Braithwaite published three volumes of his own poetry:

Lyrics of Life and Love (1904)

The House of Falling Leaves (1908)

Selected Poems (1948)

Braithwaite edited numerous poetry anthologies over the course of his career. The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia holds forty boxes of manuscripts, correspondence, and other related materials related mainly to this editorial work, in three separate Braithwaite collections.

~~~

BLAH

Saturday, March 28, 2015

Sketchbook Saturday

Since I am going in chronological order through my scanned images, this one is another from 1989. One thing about me since I am biracial and raised by my white mother and stepfather, I had a tendency to want to draw things that were particularly "ethnic" and this is one of those. It is my attempt to be very clear that the girl I am drawing from my imagination is Black without making her face super dark. I liked the challenge of being specific with the features while trying not to go overboard in any stereotype.

Saturday, March 21, 2015

Sketchbook Saturday

I drew this from a photo of myself that my mom took back in 1989. It was a snap shot that I submitted to an international model search contest. I made it to the regional semi finals. I think the region was Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas but I only remember one person from Texas and the rest were from Tucson (where I lived at the time). There may have been some girls from New Mexico and other parts of Arizona but it seemed like most of them were local.

Saturday, March 14, 2015

Sketchbook Saturday

I was constantly trying to challenge myself in one way or another when I did sketches. This one from 1989 is multiple. I was working on getting the hair and the hands. I was also practicing my face and expressions, specifically here the smile.

Saturday, March 7, 2015

Sketchbook Saturday

This pencil sketch is labeled 1989 in my files. Sometimes I would try to draw cartoon style instead of artistic or realistic. Although some would argue that cartoons are an art form! :-)

Saturday, February 28, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Georgia Douglas Johnson

|

| Georgia Douglas Johnson (image source: wikimedia) |

The closing figure of the Harlem Renaissance for my Black History Month 2015 is the writer Georgia Douglas Johnson. This is another figure that did not specifically live in Harlem yet is indelibly associated with the era.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Georgia Blanche Douglas Camp Johnson, better known as Georgia Douglas Johnson (September 10, 1880 – May 14, 1966), was an American poet, one of the earliest African-American female playwrights, and a member of the Harlem Renaissance.

Johnson's husband accepted an appointment as the Recorder of Deeds from United States President William Howard Taft, and the family moved to Washington, D.C., in 1910. It was during this period that Johnson began to write poems and stories. She credited a poem written by William Stanley Braithwaite about a rose tended by a child, as her inspiration for her poems. Johnson also wrote songs, plays, short stories, taught music, and performed as an organist at her Congregational church.

Poetry

She began to submit poems to newspapers and small magazines. Her first poem was published in 1905 in the literary journal The Voice of the Negro, though her first collection of poems was not published until 1916. She published four volumes of poetry, beginning in 1916 with The Heart of a Woman. Her poems are often described as feminine and "ladylike" or "raceless" and use titles such a "Faith", "Youth", and "Joy". Her poems appeared in multiple issues of The Crisis, a journal published by the NAACP and founded by W. E. B. Du Bois. "Calling Dreams" was published with the January 1920 edition, "Treasure" in July 1922, and "To Your Eyes" in November 1924.

Plays

Johnson wrote about 28 plays. Plumes was published under the pen name John Temple. Many of her plays were never published because of her gender and race. Gloria Hull is credited with the rediscovery of many of Johnson's plays. The 28 plays that she wrote were divided into four sections: "Primitive Life Plays", "Plays of Average Negro Life", "Lynching Plays" and "Radio Plays". Several of her plays are lost. In 1926, Johnson's play "Blue Blood" won honorable mention in the Opportunity drama contest. Her play "Plumes" also won in the same competition in 1927. Johnson was one of the only women whose work was published in Alain Locke's anthology Plays of Negro Life: A Source-Book of Native American Drama. Johnson's typescripts for ten of her plays are in collections in academic institutions.

(There is much more about her activism and work in the full wiki)

~~~

This is another female voice to add to the history of Black people in America. I find it interesting that Miss Johnson used a male pen name to bet her plays published. I have considered using a pen name sometimes just to see if it would change what people think of the words they are reading.I haven't gone through with that notion though.

Sketchbook Saturday

I am 90% sure that this pencil sketch from 1989 was drawn from a magazine picture. It was either an ad or from a fashion spread. I'm not sure which but it was definitely from a photo.

Friday, February 27, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Angelina Weld Grimké (writer)

|

| Angelina Weld Grimké (image source: wikimedia) |

Today's writer is listed in the list in the wiki on the Harlem Renaissance even though she is considered a predecessor to the era. Since she is listed in the wiki, I will include her in this series.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880 – June 10, 1958) was an African-American journalist, teacher, playwright and poet who was part of the Harlem Renaissance; she was one of the first African-American women to have a play publicly performed.

Grimké wrote essays, short stories and poems which were published in The Crisis, the newspaper of the NAACP, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois; and Opportunity. They were also collected in anthologies of the Harlem Renaissance: The New Negro, Caroling Dusk, and Negro Poets and Their Poems. Her more well-known poems include "The Eyes of My Regret", "At April", "Trees" and "The Closing Door". While living in Washington, DC, she was included among the figures of the Harlem Renaissance, as her work was published in its journals and she became connected to figures in its circle. Some critics place her in the period before the Renaissance. During that time, she counted the poet Georgia Douglas Johnson as one of her friends.

Grimké wrote Rachel – originally titled Blessed Are the Barren – one of the first plays to protest lynching and racial violence. The three-act drama was written for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which called for new works to rally public opinion against D. W. Griffith's recently released film, The Birth of a Nation (1915), which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and portrayed a racist view of blacks and of their role in the American Civil War and Reconstruction in the South. Produced in 1916 in Washington, D.C., and subsequently in New York City, Rachel was performed by an all-black cast. Reaction to the play was good. The NAACP said of the play: "This is the first attempt to use the stage for race propaganda in order to enlighten the American people relating to the lamentable condition of ten millions of Colored citizens in this free republic."

Rachel portrays the life of an African-American family in the North in the early 20th century. Centered on the family of the title character, each role expresses different responses to the racial discrimination against blacks at the time. The themes of motherhood and the innocence of children are integral aspects of Grimké's work. Rachel develops as she changes her perceptions of what the role of a mother might be, based on her sense of the importance of a naivete towards the terrible truths of the world around her. A lynching is the spectrum of the play; it authenticates the African-American experience.

The play was published in 1920, but received little attention after its initial productions. In the years since, however, its significance has been recognized as a precursor to the Harlem Renaissance, and one of the first examples of a political and cultural trend to explore the African roots of African Americans

~~~

I decided to include Angelina Weld Grimké in the series mostly because as a woman I need to see women's voices represented. In the wiki there were very few female names so I took what I could get.

Thursday, February 26, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Augusta Savage

|

| Augusta Savage (image source: wikimedia) |

I decided to finish off the month with a few more women of the Harlem Renaissance. Today we'll look at sculptor Augusta Savage.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Augusta Savage, born Augusta Christine Fells (February 29, 1892 – March 27, 1962) was an African-American sculptor associated with the Harlem Renaissance. She was also a teacher and her studio was important to the careers of a rising generation of artists who would become nationally known. She worked for equal rights for African Americans in the arts.

Augusta Fells (Savage) was born in Green Cove Springs (near Jacksonville), Florida. She began making clay figures as a child, mostly small animals, but her father would beat her when he found her sculptures. This was because at that time, he believed her sculpture to be a sinful practice, based upon his interpretation of the "graven images" portion of the Bible. After the family moved to West Palm Beach, she sculpted a Virgin Mary figure, and, upon seeing it, her father changed his mind, regretting his past actions. The principal of her new school recognized and encouraged her talent, and paid her one dollar a day to teach modeling during her senior year. This began a lifelong commitment to teaching as well as to art.

In 1907, Augusta Fells married John T. Moore. Her only child, Irene Connie Moore, was born the next year. John died shortly after. Augusta moved back in with her parents, who raised Irene with her. Augusta Fells Moore continued to model clay, and applied for a booth at the Palm Beach county fair: the initially apprehensive fair officials ended up awarding her a $25 prize, and the sales of her art totaled 175 dollars; a significant sum at that time and place.

That success encouraged her to apply to Cooper Union (Art School) in New York City, where she was admitted in October, 1921. During this time she married James Savage; they divorced after a few months, but she kept the name of Savage. She excelled in her art classes at Cooper, and was accelerated through foundation classes. Her talent and ability so impressed the staff and faculty at Cooper, that she was awarded funds for room and board, tuition being already covered for all Cooper students.

In 1923 Savage applied for a summer art program sponsored by the French government; despite being more than qualified, she was turned down by the international judging committee, solely because she was black (Bearden & Henderson, AHOAAA, p. 169-170). Savage was deeply upset, and questioned the committee, beginning the first of many public fights for equal rights in her life. The incident got press coverage on both sides of the Atlantic, and eventually the sole supportive committee member, sculptor Hermon Atkins MacNeil—who at one time had shared a studio with Henry Ossawa Tanner—invited her to study with him. She later cited him as one of her teachers. After completing studies at Cooper Union, Savage worked in Manhattan steam laundries to support herself and her family. Her father had been paralyzed by a stroke, and the family's home destroyed by a hurricane. Her family from Florida moved into her small West 137th Street apartment. During this time she obtained her first commission, for a bust of W. E. B. Du Bois for the Harlem Library. Her outstanding sculpture brought more commissions, including one for a bust of Marcus Garvey.

In 1923 Savage married Robert Lincoln Poston, a protégé of Garvey. Poston died of pneumonia aboard a ship while returning from Liberia as part of a Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League delegation in 1924.

In 1925 Savage won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome; the scholarship covered only tuition, however, and she was not able to raise money for travel and living expenses. Thus she was unable to attend.

Knowledge of Savage's talent and struggles became widespread in the African-American community; fund-raising parties were held in Harlem and Greenwich Village, and African-American women's groups and teachers from Florida A&M all sent her money for studies abroad. In 1929, with assistance as well from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, Savage enrolled and attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, a leading Paris art school. In Paris, she studied with the sculptor Charles Despiau. She exhibited and won awards in two Salons and one Exposition. She toured France, Belgium, and Germany, researching sculpture in cathedrals and museums.

(There is more in the wiki about her later works.)

~~~

As a visual artist I definitely found the story of a fellow female Black artist interesting. It somewhat makes me wish I was more serious about my own art.. We can't all be figures of Black History on a national or world wide level, but maybe I could do something on a smaller scale.

Wednesday, February 25, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Leslie Garland Bolling

|

| Leslie Garland Bolling |

Today our Harlem Renaissance figure is Leslie Garland Bolling.

~~~

From WIkipedia:

The sculptor Leslie Garland Bolling (September 16, 1898 – September 27, 1955) was born in Surry County, Virginia, United States on September 16, 1898, the son of Clinton C. Bolling, a blacksmith, and his wife Mary. His carvings reflected everyday themes and shared values of the Black culture in the segregated South in the early 20th century. Bolling was associated with the Harlem Renaissance and is notable as one of a few African-Americans whose sculpture had lasting acclaim.

|

| "Cousin on Friday" |

Bolling said he grew up near lumbering operations and was always around trees. Reportedly he enjoyed whittling which would have provided him significant experience with carving various kinds of wood. His carving seems to have been an enjoyable and somewhat profitable hobby, but he viewed himself as a porter or messenger by occupation.

His hobby seems to have taken a serious turn about the time he produced some early figures for a group exhibition sponsored by the YWCA.] About 1928 these first figures attracted the interest of Carl Van Vetchen, a patron of the Harlem Renaissance movement. He began teaching wood carving to black youth in Richmond about 1931. He taught at the Craig House Art Center in Richmond until 1941. By 1938 Bolling and others had obtained WPA sponsorship for the Craig House. It was the only WPA sponsored art center in the segregated South for black youth.

His work began to achieve broader recognition as a result of the National Negro Exhibition of 1933 at the Smithsonian. Bolling participated in a number of art tours between 1934 and 1940, managed by the Harmon Foundation to showcase the artistic work of African-Americans.

Reflecting the growing significance of his sculpture, in January 1935, Bolling was honored when the then segregated Academy of Arts in Richmond, now the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts produced a one-man show of his carvings. This was followed by a show at the New Jersey state museum. Thomas Hart Benton was interested in his work and visited the extended show.

(images from wikimedia)

~~~

I really wish that I had studied more Black artists before now. I really enjoyed learning about a simple man who had a hobby that he turned into viable art.

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

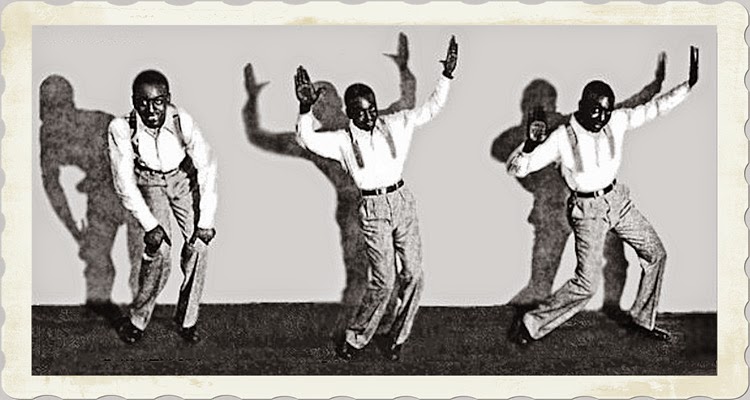

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Billy Pierce

Only a few more days are left in February! Today's figure from the Harlem Renaissance is Billy Pierce. I couldn't find an actual picture of him so I had to settle for the cover of the sheet music above.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Billy Pierce (14 June 1890 – 11 April 1933) was an African American choreographer, dancer and dance studio owner who has been credited with the invention of the Black Bottom dance that became a national craze in the mid-1920s.

The Billy Pierce Dance Studio flourished and became one of the incubators for the cultural flowering know to posterity as the Harlem Renaissance. By 1929, Pierce's studio—the "largest of its kind" according to the Afro American newspaper—occupied five rooms in the bottom two floors of the building, for which Pierce paid annually $6,000 in rent (equivalent to approximately $82,407 in 2015 dollars

Pierce ran the studio and coached Broadway stars, but did not serve as an instructor for the 27 classes that were given to students in 1929. The Pierce Dance Studio was the professional home of his fellow African American choreographer Buddy Bradley, who devised dance routines for the eccentric dancer Tom Pericola, a white man. Pericola performed the Black Bottom with the Ann Pennington in the musical-comedy revue George White's Scandals of 1926 on Broadway, whereupon it became popular eventually supplanting Charleston on dance floors across America.

Along with the Black Bottom and the Charleston, among the specialities of the Billy Pierce Dance Studio were the Black Bottom with Taps, the Eccentric Buck and the Syncopated Buck, the Devil Dance, the Dirty Dig, the Flapper Stomp, the Harlem Hips, the Jungle Stomp, the Stair Dance, and the Zulu Stomp.

In the United States, African American choreographers like Pierce and Bradley generally worked uncredited. They also coached and developed routines for white performers, such as Bradley had coached Pericola. Before he became an Oscar-winning character actor, Clifton Webb was a song and dance man on Broadway, appearing in many musicals. He honed his dancing skills at Pierce's studio. Pierce developed the "Moaning Low" dance routine for "Cliff" Webb, as he was then known, and Libby Holman for The Little Show in 1931.

Along with Benny Rubin, Pierce did the choreography for the 1927 musical Half a Widow, one of the few Broadway shows for which he received credit. He also created "The Sugar Foot Strut" dance for the smash hit musical Rio Rita (1927) and developed a show-stopping routine for[Norma Terris, who played Magnolia in the original 1927 production of Show Boat and its 1932 revival. He also got credit for choreographing the dances in the 1932 musical revue Walk a Little Faster.

In 1930, he spent eleven months in Europe, working with directors such as Max Rheinhardt.

~~~

Since Billy Pierce was mainly behind the scenes and only known to people truly into the dance of the era, I had not heard of him before. I hadn't heard of the Black Bottom dance either. I wish there was pictures or film of Billy Pierce himself.

Monday, February 23, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Leonard Harper

|

| Leonard Harper and the Harperettes |

image source: http://blackamericaweb.com/2014/02/18/little-known-black-history-fact-leonard-harper-and-the-harperettes/

To continue the series on the Harlem Renaissance, today we will look at the producer Leonard Harper.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Leonard Harper was a producer/stager/choreographer in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s born on April 9, 1899 in Birmingham, Alabama

Leonard Harper's works spanned the worlds of Vaudeville, Cabaret, Burlesque and Broadway musical comedy. As a dancer, choreographer and studio owner, he coached many of the country’s leading performers, including Ruby Keller, Fred Astaire and Adele Astaire, and the Marx Brothers.

His father, William Harper, was a performer. Leonard Harper started dancing as a child to attract a crowd on a medicine show wagon, traveling with the show throughout the South. In 1915, Harper first came to New York City, but quickly moved to Chicago and began choreographing and performing dance acts with Osceola Blanks of the Blanks Sisters, whom he married in 1923.

Leonard Harper and Osceola Blanks performed in his first big revue, Plantation Days when it opening at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem in 1922-1923, and began producing floor shows in Harlem and New York thereafter.

In 1923-1924, Leonard offered the Duke Ellington orchestra the house band position at the speakeasies, Connie’s Inn in Harlem and the Kentucky Club in Times Square, where we has producing shows, and the Duke Ellington orchestra played as the house band at the Kentucky Club for the next for years.

By 1925, Leonard owned a Times Square dance studio where black dancers taught white performers black dances.

As a nightclub and Broadway producer, he counted Billie Holiday, Ethel Waters, Duke Ellington, Bill Robinson and Count Basie among his colleagues. He introduced Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway to New York show business, and worked with Mae West, Josephine Baker, Lena Horne, Fats Waller and Eubie Blake.

Leonard Harper was part of the transition team when the Deluxe Cabaret was turned into the Cotton Club, producing two of its first revues during its opening.

Leonard Harper’s biggest milestone on the Great White Way was his staging of the Broadway hit “Hot Chocolates”, which made the songs “Black and Blue” and “Ain’t Misbehavin” classic Broadway show tunes.

Mr. Harper was one of the leading figures who transformed Harlem into a cultural center during the 1920s. His nightclub productions took place at Connie’s Inn, the Lafayette Theatre (Harlem) at the opening of the new Apollo Theatre, and at other theaters in New York.

Leonard Harper died in Harlem, NY, on Thursday February 4th, 1943.

Sunday, February 22, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - The Nicholas Brothers

To continue with the dancers of the era of the Harlem Renaissance, today we will look at the Nicholas brothers.

~~~

from Wikipedia

The Nicholas Brothers were an African-American team of dancing brothers, Fayard (1914–2006) and Harold (1921–2000), who performed a highly acrobatic technique known as "flash dancing". With a high level of artistry and daring innovations, they were considered by many to be the greatest tap dancers of their day.

Growing up surrounded by vaudeville acts as children, they became stars of the jazz circuit during the heyday of the Harlem Renaissance and went on to have successful careers performing on stage, film, and television well into the 1990s.

~~~

The first glimpse of the Nicholas brothers I ever had (since I have not watched many classic Black movies) was a link someone posted a few months back (see link below). They were EXTREME in their way of moving across the screen. I would imagine to see them on stage would have been intense!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DF3KOLS9qLg

Saturday, February 21, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Bill "Bojangles" Robinson

|

| Bill "Bojangles" Robinson (May 25, 1878 – November 25, 1949) |

Although Bojangles' time in Harlem was brief and seems to only be in the context of stops on his tours, he is included by the wiki author as part of the Harlem Renaissance. I have included him in this series for that reason and because he is a well known performer of the time frame.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Bill "Bojangles" Robinson (May 25, 1878 – November 25, 1949) was an American tap dancer and actor, the best known and most highly paid African American entertainer in the first half of the twentieth century. His long career mirrored changes in American entertainment tastes and technology, starting in the age of minstrel shows, moving to vaudeville, Broadway, the recording industry, Hollywood radio, and television. According to dance critic Marshall Stearns, “Robinson's contribution to tap dance is exact and specific. He brought it up on its toes, dancing upright and swinging,” giving tap a “…hitherto-unknown lightness and presence.”[1]:pp. 186–187 His signature routine was the stair dance, in which Robinson would tap up and down a set of stairs in a rhythmically complex sequence of steps, a routine that he unsuccessfully attempted to patent. Robinson is also credited with having introduced a new word, copacetic, into popular culture, via his repeated use of it in vaudeville and radio appearances.

A popular figure in both the black and white entertainment worlds of his era, he is best known today for his dancing with Shirley Temple in a series of films during the 1930s, and for starring in the musical Stormy Weather (1943), loosely based on Robinson's own life, and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. Robinson used his popularity to challenge and overcome numerous racial barriers, including becoming the following:

one of the first minstrel and vaudeville performers to appear without the use of blackface makeup

one of the earliest African American performers to go solo, overcoming vaudeville's two colored rule

a headliner in the first African-American Broadway show, Blackbirds of 1928

the first African American to appear in a Hollywood film in an interracial dance team (with Temple in The Little Colonel)

the first African American to headline a mixed-race Broadway production

During his lifetime and afterwards, Robinson also came under heavy criticism for his participation in and tacit acceptance of racial stereotypes of the era, with critics calling him an Uncle Tom figure. Robinson resented such criticism, and his biographers suggested that critics were at best incomplete in making such a characterization, especially given his efforts to overcome the racial prejudice of his era. In his public life Robinson led efforts to:

persuade the Dallas police department to hire its first African American policemen

lobby President Roosevelt during World War II for more equitable treatment of African American soldiers

stage the first integrated public event in Miami, a fundraiser which, with the permission of the mayor, was attended by both black and white city residents

Despite being the highest-paid black performer of the era, Robinson died penniless in 1949, and his funeral was paid for by longtime friend Ed Sullivan. Robinson is remembered for the support he gave to fellow performers, including Fred Astaire, Lena Horne, Jesse Owens, and the Nicholas brothers. Both Sammy Davis, Jr. and Ann Miller credit him as a teacher and mentor, and Miller credits him with having “changed the course of my life.” Gregory Hines produced and starred in a biographical movie about Robinson for which he won the NAACP Best actor Award. In 1989, the U.S. Congress designated May 25, Robinson's birthday, as National Tap Dance Day.

~~~

The interesting thing is that the above is just the intro to the wiki! I haven't really watched the full repertoire of Bojangles but my passing awareness of him was as a minstrel performer along the lines of Steppin Fetchit bur with more style (his tap routine in Shirley Temple movies for example). From what little I have read of him, I think the folks in Harlem probably regarded him in much the same way. In spite of that it is notable that he did break a lot of barriers in the entertainment industry as a Black man in the time when he was "colored" or "negro" at best. In a sense, he paved the way for the artists of the jazz movement that the Harlem Renaissance is most known for. He may have played "safe" roles for his skin tone, but what actor even today doesn't? Plus he did the roles with a dignity that Steppin did not (in my opinion).

Sketchbook Saturday

I don't remember if I drew this back in 1989 from a magazine photo or from my imagination or a combination of both. I do know that I was always trying to push myself and try to draw things I found difficult. I still find doing a whole person difficult. I think I did a decent job here.

Friday, February 20, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Buddy Bradley

|

| Buddy Bradley |

(image source: http://bohemiajam.weebly.com/ )

I had been going down the list of "Leading Intellectuals" of the Harlem Renaissance in the Wikipedia article, but the rest of the people listed are poets and I think I will save that for April and National Poetry Month. So I am going to go back to where I left off when I started the posts on notable persons with Josephine Baker. I'll be going back to the dancers, choreographers, and other entertainers and doing choreographer Buddy Bradley today.

The Wikipedia article for Buddy Bradley is not very good so I searched for other information and found the following items:

http://buddybradley.taplegacy.org/biography/

http://www.vam.ac.uk/users/node/9091 (from the UK)

http://www.streetswing.com/histmai2/d2budbrd1.htm

The abridged version is that Buddy was born aproximately 1908 and moved to the state of New York due to the death of his mother when he was a teen. When he was of age, he moved to New York City and that was where he came into the dance industry even though he was self taught and not trained in any school. Because of his color, he was never given credit for the moves he created and taught to white dancers in shows so he relocated to Great Britain and there he found the credit and open respect he deserved.

I like what the UK link said in the short paragraph:

Great dance teachers are rarer than great performers but are often unknown outside the dance world. British dance's debt to teacher and choreographer Buddy Bradley is huge. He brought American attack and professionalism to English dance in 1930s musicals. The list of stars who worked with him, either training or working out their routines, is breathtaking. In England they included [Jack Buchanan] Jessie Matthews, Anna Neagle, Jack Hulbert, and Elsie Randolph and in America, Fred Astaire and Eleanor Powell. This rare article [shown in the link] gives an insight into his teaching and an idea of the respect in which he was held within the profession.

Sadly, the image in the link when enlarged is too small to read the article it mentions.

Thursday, February 19, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Nella Larsen

|

| Nella Larsen (image source: wikimedia) |

The next "leading intellectual" we will look at from the Harlem Renaissance is another female writer Nella Larsen.

~~~

From WIkipedia:

Nellallitea "Nella" Larsen, born Nellie Walker (April 13, 1891 – March 30, 1964), was an American novelist of the Harlem Renaissance. First working as a nurse and a librarian, she published two novels—Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929)—and a few short stories. Though her literary output was scant, she earned recognition by her contemporaries. A revival of interest in her writing has occurred since the late twentieth century, when issues of racial and sexual identity and identification have been studied.

Nella Larsen was born Nellie Walker in Chicago on April 13, 1891, the daughter of Peter Walker, an Afro-Caribbean immigrant from the Danish West Indies and Marie Walker, née Hansen, a Danish immigrant. Her mother was a seamstress and domestic worker. Her father soon disappeared from her life, and her mother married Peter Larsen, a fellow Danish immigrant, by whom she had another daughter. Nellie took her stepfather's surname, sometimes using versions spelled as Nellye Larson, Nellie Larsen and, finally, settling on Nella Larsen. The mixed family encountered discrimination among the ethnic white immigrants in Chicago of the time.

In 1921 Larsen worked nights and weekends as a volunteer with Ernestine Rose, to help prepare for the first exhibit of "Negro art" at the New York Public Library (NYPL). Encouraged by Rose, she became the first black woman to graduate from the NYPL Library School, which was run by Columbia University.

Larsen passed her certification exam in 1923 and spent her first year working at the Seward Park Branch on the Lower East Side, where she had strong support from her white supervisor Alice Keats O'Connor, as she had from Rose. They, and another branch supervisor where she worked, supported Larsen and helped integrate the staff of the branches. She next transferred to the Harlem branch, as she was interested in the cultural excitement in the neighborhood.

In October 1925, Larsen took a sabbatical from her job for health reasons and began to write her first novel. In 1926, having made friends with important figures in the Negro Awakening (which became the Harlem Renaissance), Larsen gave up her work as a librarian.

She became a writer active in Harlem's interracial literary and arts community, where she became friends with Carl Van Vechten, a white photographer and writer. In 1928, Larsen published Quicksand, a largely autobiographical novel, which received significant critical acclaim, if not great financial success.

In 1929, she published Passing her second novel, which was also critically successful. It dealt with issues related to two mixed-race women who were friends and had taken different paths of racial identification and marriage. One married a man who identified as black, and the other a white man. The book explored their experiences of coming together again as adults.

In 1930, Larsen published "Sanctuary", a short story for which she was accused of plagiarism. "Sanctuary" was said to resemble Sheila Kaye-Smith’s short story, "Mrs. Adis", first published in the United Kingdom in 1919. Kaye-Smith wrote on rural themes, and was very popular in the US. Some critics thought the basic plot of "Sanctuary," and some of the descriptions and dialogue, were virtually identical to her work.

The scholar H. Pearce has taken issue with this assessment, writing that, compared to Kaye-Smith’s tale, "Sanctuary" is '... longer, better written and more explicitly political, specifically around issues of race - rather than class as in "Mrs Adis". Pearce thinks that Larsen reworked and updated the tale into a modern American black context. Pearce also notes that in her 1956 book, All the Books of My Life, Kaye-Smith said she had based "Mrs Adis" on an old story by St Francis de Sales. It is unknown whether she knew of the Larsen controversy.

No plagiarism charges were proved. Larsen received a Guggenheim Fellowship in the aftermath of the criticism. She used it to travel to Europe for several years, spending time in Mallorca and Paris, where she worked on a novel about a love triangle, in which all the protagonists were white. She never published the book or any other works.

Larsen returned to New York in 1933, when her divorce had been completed. She lived on alimony until her ex-husband's death in 1942. Struggling with depression, Larsen was not writing (and never would again). After her ex-husband's death, Larsen returned to nursing. She disappeared from literary circles. She lived on the Lower East Side, and did not venture to Harlem.

Many of her old acquaintances speculated that she, like some of the characters in her fiction, had crossed the color line to "pass" into the white community. The biographer George Hutchinson has demonstrated in his 2006 work that she remained in New York, working as a nurse. She avoided contact with her earlier friends and world.

Larsen died in her Brooklyn apartment in 1964, at the age of 72.

~~~

I had not heard of Nella Larsen before embarking on this Black History Month examination of the Harlem Renaissance. I guess I have a LOT of reading to look forward to when I get a break in my homework from school!

Wednesday, February 18, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Zora Neale Hurston

.jpg) |

| Zora Neale Hurston (image source: wikimedia) |

I've been doing the names mostly in order that they appear in the Harlem Renaissance wiki and it took until now to get to a female voice of the era.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Zora Neale Hurston (January 7, 1891 – January 28, 1960) was an American folklorist, anthropologist, and author. Of Hurston's four novels and more than 50 published short stories, plays, and essays, she is best known for her 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

In addition to new editions of her work being published after a revival of interest in her in 1975, her manuscript Every Tongue Got to Confess (2001), a collection of folktales gathered in the 1920s, was published posthumously after being discovered in the Smithsonian archives.

(The wiki is very extensive so I am only putting the intro here. I suggest reading it in full to get all the information and history on this amazing woman.)

~~~

I had heard the name Zora Neale Hurston, but I haven't really explored her works. There is so much to her that I didn't want to paste the whole wiki here. I guess I now have some homework to find some of her work and read it!

Tuesday, February 17, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - W. E. B. Du Bois

|

| W. E. B. Du Bois (iimage source: wikimedia) |

W. E. B. Du Bois is another figure who did not live in Harlem but was a nationally influential figure during the era and is listed in the "Leading Intellectuals" list of the wiki so I am including him here as well.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

William Edward Burghardt "W. E. B." Du Bois (pronounced /duːˈbɔɪz/ doo-boyz; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author and editor. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community. After graduating from Harvard, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. Du Bois was one of the co-founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Du Bois rose to national prominence as the leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists who wanted equal rights for blacks. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta compromise, an agreement crafted by Booker T. Washington which provided that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic educational and economic opportunities. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the Talented Tenth and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership.

Racism was the main target of Du Bois's polemics, and he strongly protested against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for independence of African colonies from European powers. Du Bois made several trips to Europe, Africa and Asia. After World War I, he surveyed the experiences of American black soldiers in France and documented widespread bigotry in the United States military.

Du Bois was a prolific author. His collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, was a seminal work in African-American literature; and his 1935 magnum opus Black Reconstruction in America challenged the prevailing orthodoxy that blacks were responsible for the failures of the Reconstruction Era. He wrote the first scientific treatise in the field of sociology; and he published three autobiographies, each of which contains insightful essays on sociology, politics and history. In his role as editor of the NAACP's journal The Crisis, he published many influential pieces. Du Bois believed that capitalism was a primary cause of racism, and he was generally sympathetic to socialist causes throughout his life. He was an ardent peace activist and advocated nuclear disarmament. The United States' Civil Rights Act, embodying many of the reforms for which Du Bois had campaigned his entire life, was enacted a year after his death.

~~~

I'll be honest, even though WEB DuBois has always been a name I have heard every black history month, and is someone who I am certain that in my past I had read up on him, I still feel like my knowledge of him lacks a fullness. I had a basic awareness of him as one of the founders of the NAACP and as a prolific activist and political writer, but really I guess that is a decent concise summary of the above.

Monday, February 16, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Marcus Garvey

|

| Marcus Garvey (image source: wikimedia) |

Although Marcus Garvey didn't live in Harlem, he is listed as one of the prominent intellectuals of the era. I'm guessing this is because his ideas greatly influenced many Blacks around the world at that time. For this reason I am including him in this series.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr., ONH (17 August 1887 – 10 June 1940), was a Jamaican political leader, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator who was a staunch proponent of the Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism movements, to which end he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL).[2] He founded the Black Star Line, which promoted the return of the African diaspora to their ancestral lands.

Prior to the twentieth century, leaders such as Prince Hall, Martin Delany, Edward Wilmot Blyden, and Henry Highland Garnet advocated the involvement of the African diaspora in African affairs. Garvey was unique in advancing a Pan-African philosophy to inspire a global mass movement and economic empowerment focusing on Africa known as Garveyism.[2] Promoted by the UNIA as a movement of African Redemption, Garveyism would eventually inspire others, ranging from the Nation of Islam to the Rastafari movement (which proclaims Garvey as a prophet).

Garveyism intended persons of African ancestry in the diaspora to "redeem" the nations of Africa and for the European colonial powers to leave the continent. His essential ideas about Africa were stated in an editorial in the Negro World entitled "African Fundamentalism", where he wrote: "Our union must know no clime, boundary, or nationality… to let us hold together under all climes and in every country…"

~~~

My first hint of hearing about Marcus Garvey was back in the 80s when I was in High School and what I thought I knew was that he was a separatist and had a "Back to Africa" type movement. I later learned of the Rastafarian view of him in the early 2000s (about 2002 or so). Having since dated a full on Jamaican style dread-locked Rasta, I have heard a few of the speeches but honestly have never really felt an affinity with the ideology. I guess I am just too American for all that.

Sunday, February 15, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Arturo Alfonso Schomburg

|

| Arturo Alfonso Schomburg |

Day 15 of this exploration of the Harlem Renaissance we look at Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. He is yet another figure that has an extensive wiki article so I will just post a short intro here:

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, also Arthur Schomburg (January 24, 1874 – June 8, 1938), was a Puerto Rican historian, writer, and activist in the United States who researched and raised awareness of the great contributions that Afro-Latin Americans and Afro-Americans have made to society. He was an important intellectual figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Over the years, he collected literature, art, slave narratives, and other materials of African history, which was purchased to become the basis of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, named in his honor, at the New York Public Library (NYPL) branch in Harlem.

~~~

Schomburg is another figure like L.S. Alexander Gumby who took the time to collect documentation of the history of Americans of African decent to preserve our unique narrative on this continent. I am so intrigued by these figures and their dedication to keeping our story. It makes me wonder if Johnson Publishing even took people like these and how valuable their contribution was into consideration when they decided to sell their archives. I really wish they would open some kind of museum like what was done with Schomburg's and Gumby's legacy.

Saturday, February 14, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Joel Augustus Rogers

|

| Joel Augustus Rogers |

Today's look at Harlem Renaissance leading intellectuals is Joel Augustus Rogers. The Wikipedia article on him is quite extensive so I am just putting a very brief intro here:

Joel Augustus Rogers (September 6, 1880 or 1883 – March 26, 1966) was a Jamaican-American author, journalist, and historian who contributed to the history of Africa and the African diaspora, especially the history of African Americans in the United States. His research spanned the academic fields of history, sociology and anthropology. He challenged prevailing ideas about race, demonstrated the connections between civilizations, and traced African achievements. He was one of the greatest popularizers of African history in the 20th century.

~~~

I would definitely suggest reading the whole wiki. Rogers was definitely a very prolific author of his day and now I have a whole list of new things to look up to read!

Sketchbook Saturday

This pencil sketch is from 1989. I don't have a clever story for this one other than if you look close you can tell that the picture I did on another page either bled through or transferred. You can see where it says "BLOODS 2 Da <3" which is a hint at the social group I was around at the time. I didn't bang myself but my cousin from Cali and the friends she managed to make did and I ended up getting friends through her instead of vice versa. I was the goodie two shoes little sis of the crew. The interesting and/or ironic thing is that only 50% of the gang bangers I knew in Tucson, Arizona back then were Black. Most were white or Hispanic and even one Asian. I know that this side story is irrelevant to the art shown, but I figured since it was there I would expound.

Friday, February 13, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Chandler Owen

|

| Chandler Owen |

(Image source: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/owen-chandler-1889-1967)

We are nearly halfway through the month and not even close to halfway through the list of prominent intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance. Today we'll look at Chandler Owen.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Chandler Owen (1889–1967) was an African-American writer, editor and early member of the Socialist Party of America. Born in North Carolina, he studied and worked in New York, then moved to Chicago for much of his career. He established his own public relations company in Chicago and wrote speeches for candidates and presidents including Thomas Dewey, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Owen was born in Warrenton, North Carolina, in 1889. He graduated from Virginia Union University in 1913. Later, while studying economics at Columbia University in 1916, he joined the Socialist Party of America. He began a lifelong friendship with A. Philip Randolph and together they followed the lead of radical activist Hubert Harrison. They soon became known in Harlem as "Lenin" (Owen) and "Trotsky" (Randolph). The two started a journal in 1917, called The Messenger, which published leading literary and political writers. Soon after, while Owen was running for the New York State Assembly, he and Randolph were jailed, where they were mocked and treated cruelly for their Socialist affiliations.

Owen moved to Chicago, Illinois, shortly thereafter and found himself quickly enlightened with socialistic views. He became managing editor of the Chicago Bee, a major African-American publication, and continued to back Randolph in his efforts to unionize Pullman porters on the railroads. With his mounting career success, Owen went on to establish his own public relations company. He remained interested in politics and wrote many speeches for politicians such as Wendell Willkie, Thomas Dewey, and even for US presidents Dwight Eisenhower and Lyndon B. Johnson.

In the 1920s, Owen became a Republican. He would later ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. For the remainder of his life, he worked in public relations and continue to write speeches.

Suffering from terminal kidney disease, Owen wrote a last letter to Philip Randolph saying, "Our long friendship, never soiled, is nearing its close. I've been in pain. If you were not living, I would commit suicide today." Owen died soon after in November 1967.

Like Harrison and Randolph, Owen was an atheist. In a 1919 issue of The Messenger he and Randolph wrote, "We don't thank God for anything...our Deity is the toiling masses of the world and the things for which we thank are their achievement."

~~~

I have to admit that I am not really an intellectual in the strictest sense. I do read from time to time (voraciously in spurts), but reading about the more politically active intellects of this era definitely makes me realize that I am only somewhat smart and not really a radical or on an upper echelon. I find it interesting to read about these people that I may have heard of before but don't necessarily know anything about.

Thursday, February 12, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Charles Spurgeon Johnson

|

| Charles Spurgeon Johnson |

image source: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/johnson-charles-s-1893-1956

So on this 12th day of February, the examination of the Harlem Renaissance intellectual leaders continues with Charles Spurgeon Johnson.

~~~

From http://www.blackpast.org/:

Charles Spurgeon Johnson, one of the leading 20th Century black sociologists, was born in Bristol, Virginia on July 24, 1893. After receiving his B.A. from Virginia Union University in Richmond, he studied sociology with the noted sociologist Robert E. Park at the University of Chicago, Illinois where he earned a Ph.D. in 1917. Initially a friend of historian Carter G. Woodson, he did collaborative work with the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History until his relationship with Woodson deteriorated.

Johnson, however, was able to attract research funding from white philanthropic organizations such as the General Education Board, Phelps-Stokes Fund, Rosenwald Fund, and the Rockefeller Foundation which allowed him to study the social condition of Black communities suffering under Jim Crow. That research ensured that Johnson would emerge by the 1920s as the nation's foremost scholar in the field of Black Sociology.

Surviving and being a witness to the race riots during the Red Summer of 1919, Johnson investigated the causes of the riots and produced an assessment for the Chicago Commission on Race Relations. His research ultimately became The Negro in Chicago, the first of numerous published 20th Century studies of the cause’s urban riots and their consequences. This highly acclaimed study led in 1921 to Dr. Johnson being appointed director of research for the National Urban League. In 1923 Johnson founded its professional magazine, Opportunity, and became its first editor. Opportunity published a wide variety of social science research and popular essays which revealed the impact Jim Crow on the African American community at that time.

In 1928, Dr. Johnson decided to move to Fisk University to continue his research and to become its first chairman of the newly established Department of Social Sciences. He viewed the move to a black institution as strengthening his scholarly work by enabling him to acquire more white philanthropic research funding. Upon receiving the funding he expected Johnson established the Fisk Institute of Race Relations, first "think tank" at a predominantly black institution. In recognition of his efforts to place Fisk University on the academic map, the institution's board of trustees, in 1948, appointed him the first black president of Fisk University. Dr. Johnson served in this capacity, did further innovative research, and received many accolades and honors until his death in Nashville, Tennessee on October 27, 1956.

~~~

It is amazing to read about the way this man was able to navigate the American intellectual landscape as Negro/colored in that era. I also find it interesting to know that as late as 1948, Fisk as a Black institution had never had a Black president.

I chose to look at the intellectuals first this month because it would be easy for me as a poet and performer to focus on the poetry, music, dance, and theater which seems to be the primary focus of many of the things I have seen or read in the past. Even though I may not relate as much to the college and self-educated activists of the day as to the performers, as a sometime activist myself I feel that it is good for me to look at what others have accomplished.

Wednesday, February 11, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Hubert Harrison

I have mentioned Hubert Harrison in the 2nd installment this month but I felt like that tiny mention wasn't enough and decided to give him his own entry.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Hubert Henry Harrison (April 27, 1883 – December 17, 1927) was a West Indian-American writer, orator, educator, critic, and radical socialist, and Single-Tax political activist based in Harlem, New York. He was described by activist A. Philip Randolph as “the father of Harlem radicalism” and by the historian Joel Augustus Rogers as “the foremost Afro-American intellect of his time.” John G. Jackson of American Atheists described him as "The Black Socrates".

An immigrant from St. Croix at the age of 17, Harrison played significant roles in the largest radical class and race movements in the United States. In 1912-14 he was the leading Black organizer in the Socialist Party of America. In 1917 he founded the Liberty League and The Voice, the first organization and the first newspaper of the race-conscious “New Negro” movement. From his Liberty League and Voice came the core leadership of individuals and race-conscious program of the Garvey movement.

Harrison was a seminal and influential thinker who encouraged the development of class consciousness among working people, positive race consciousness among Black people, agnostic atheism, secular humanism, social progressivism, and freethought. He was also a self-described "radical internationalist" and contributed significantly to the Caribbean radical tradition. Harrison profoundly influenced a generation of “New Negro” militants, including A. Philip Randolph, Chandler Owen, Marcus Garvey, Richard Benjamin Moore, W. A. Domingo, Williana Burroughs, and Cyril Briggs.

Harrison came to New York in 1900 as a 17-year-old orphan and joined his older sister. He confronted a racial oppression unlike anything he previously knew, as only the United States had such a binary color line. In the Caribbean, social relations were more fluid. Harrison was especially “shocked” by the virulent white-supremacy typified by lynchings, which were reaching a peak in these years in the South. They were a horror that had not existed in St. Croix or other Caribbean islands. In addition, the fact that in most places blacks and people of color far outnumbered whites meant they had more social spaces in which to operate away from the oversight of whites.

In the beginning, Harrison worked low-paying service jobs while attending high school at night. For the rest of his life, Harrison continued to study as an autodidact. While still in high school, his intellectual gifts were recognized. He was described as a “genius” in The World, a New York daily newspaper. At age 20, he had an early letter published by the New York Times in 1903. He became an American citizen and lived in the United States the rest of his life.

~~~

One thing I didn't know before reading the Wikipedia information is that Harrison had influenced Marcus Garvey who was the influencer of so many people from his day to now. I'm sure people who sutdy Garvey probably already knew that but for me as a mainstream person with limited education on Black History I found that tidbit very interesting.

I also found it interesting that Harrison coming from St Croix had a culture shock of how divided the races were in the USA. I can relate. As a person who grew up in Arizona I found NYC in general to be deeply divided and segregated along color lines even in 1998. I lived in a world where everyone mixed together and most of us really didn't think about it, but in NYC the divisions were clear and maintained for all groups: Italians, Puerto Ricans (and some other island Latinos), Carribean Blacks, Southern Blacks, Northern Blacks. It was so foreign to me.

The next step of course is to try and find some of his works and study him further but for now this snippet is way more than I ever knew before.

Tuesday, February 10, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - L.S. Alexander Gumby

.jpg) |

| LS Alexander Gumby (circa 1950) |

There are a lot of names in the category "Leading Intellectuals" in the Wikipedia article on the Harlem Renaissance. Some of the names that I have always associated with the late 1800s are included such as WEB DuBois and Marcus Garvey which accentuates the incompleteness of my public school education and the limitations of my biracial upbringing in Arizona. I decided to highlight the names I was unfamiliar with to supplement my personal education. Today's figure is L.S. Alexander Gumby.

~~~

Part of the information from Wikipedia:

Levi Sandy Alexander Gumby (February 1, 1885 – March 16, 1961) was an African-American archivist and historian. His collection of 300 scrapbooks documenting African-American history have been part of the collection of Columbia University since 1950 as the Alexander Gumby Collection of Negroiana. Gumby was also the proprietor of a popular bookstore during the Harlem Renaissance, where he was host of a salon. Gumby's passion for collecting earned him the nicknames "The Count" and "Mr. Scrapbook".

In the 1920s Gumby received financial assistance to help compile his collection from Charles W. Newman, a wealthy stockbroker. With Newman's help Gumby moved his collection to a large studio at 2144 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan's Harlem district, that became known as "Gumby's Bookstore". His book studio became an important gathering place for the figures of the Harlem Renaissance.

The book studio served as a workspace to compile the collection as well as an exhibition space, and an artistic and intellectual salon. Due to the imperious nature with which he conducted his salon he was nicknamed "The Great God Gumby".

In September 1901, aged 16, Gumby made his first scrapbook with clippings concerning the assassination of President McKinley. Gumby had organized his clippings by 1910, and took his archival work seriously, visiting similar collections in libraries across the United States and Canada. Gumby also became acquainted with fellow African-American archivist, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Working as a waiter at Columbia University Gumby began fraternizing with academia and students, adding clippings to his collection about popular professors and Columbia's president, Nicholas Murray Butler. In 1925 Gumby's collection so crowded his 2½ rooms that he was forced to lease the entire second-floor unpartitioned apartment of the house in which he lived. Gumby initially found it easy to acquire his collection as "Negro" items were considered of little interest to book dealers.

The scrapbooks contain autographed photos, stories and letters from such notable performers as Paul Robeson, Josephine Baker, Langston Hughes, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie and Ethel Waters, and letters and autographs from Black historical figures such as Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Father Divine, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Marcus Garvey.

Gumby kept collecting while hospitalized, including articles about his hospitalization, get-well cards and photographs of friends who visited him. Upon his release from hospital Gumby retrieved and began restoring his collection, and continued to add to them. In 1950 Gumby donated his collection to Columbia University and in 1951, Columbia hired him for eight months to help organize the collections. Gumby continued to add to his scrapbooks until his death from complications from tuberculosis in 1961. The 300 scrapbooks are part of Columbia's Rare Book and Manuscript Library in Butler Library as the Alexander Gumby Collection of Negroiana

~~~

I have to say that I find the very idea of Gumby's scrapbook collection intriguing, and the name "Negroiana" to be very amusing to my 21st century mind. I hope that I get a chance to visit the collection someday. I guess it will have to wait until after I finish the sailing trip around the world.

Monday, February 9, 2015

Black History Month 2015 - The Harlem Renaissance - Cyrill Briggs

|

| Cyrill Briggs and Charlene Mitchell, 1960 |

image source: http://www.blackpast.org/aah/briggs-cyril-1888-1966

Today I'm continuing with the series on leading intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance with Cyrill Briggs.

~~~

From Wikipedia:

Cyril Valentine Briggs (1888-1966) was an African-Caribbean American writer and communist political activist. Briggs is best remembered as founder and editor of The Crusader, a seminal New York magazine of the New Negro Movement of the 1920s and as founder of the African Blood Brotherhood, a small but historically important radical organization dedicated to advancing the cause of Pan-Africanism.

From www.blackpast.org

Cyril Briggs was a pioneering civil rights activist, journalist, black nationalist, and member of the American Communist Party. Born in 1888 on the Eastern Caribbean island of Nevis, Briggs immigrated to New York City in 1905 and joined a burgeoning community of radical West Indian intellectuals in Harlem. In 1912 be was hired at the New York Amsterdam News where he voiced support for World War I and Woodrow Wilson's anti colonial doctrine of self-determination, which he saw as validating his own radical vision of African American self-rule. Further radicalized in the wake of World War I and the Russian Revolution, Briggs started publishing his own periodical, the Crusader, in September 1918 and one month later founded the African Blood Brotherhood (ABB). Incorporating Marxist class-consciousness under the banner of "Africa for Africans," the Crusader and the ABB became vehicles for Briggs' distinctive merger of interracial revolutionary socialism with black nationalism and anti colonialism.

In 1921 Briggs formally joined the nascent American Communist Party (CP). As the ABB increasingly merged ideologically and organizationally with the CP, Briggs, along with fellow Harlem radicals Otto Huiswood and Claude McKay, became a critical bridge between black communities and the Communist movement, an association that would grow in both numbers and significance over the next two decades. Briggs' conversion to revolutionary socialism drew him into a public feud with Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association in the early 1920s. Briggs castigated Garvey's brand of black nationalism for its capitalist overtones and ultimately cooperated with federal authorities investigating Garvey for mail fraud. Briggs' influence in Party circles declined rapidly in mid decade as the CP shifted its focus away from the community based revolutionary nationalism of the ABB and toward the labor movement and the newly formed American Negro Labor Congress.

Despite a brief resurgence in 1929, when he assumed a major role in directing the Party's campaign against vestiges of racial chauvinism within Party ranks, Briggs was increasingly marginalized and accused of sectarianism. Briggs' removal from the editorship of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights' Harlem Liberator in 1933 and the Party's ideological turn toward the Popular Front in the mid 1930s effectively signaled the end of his influence in radical politics.

~~~

I have to be honest and say that I had not heard of Cyrill Briggs before. My knowledge of the era is pretty much limited to figures like Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Josephine Baker, and Zora Neal Hurston and a few of the jazz artists of the day like Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday.

Looking at the world politics of the era and how since the system didn't really include Blacks in the process, I can see how many intellectuals leaned towards Socialism and Communism and other alternate forms of political expression. Seeing it from this side of history, it's a bit sad that the ideologies of Russia and other eastern European countries that spoke to "the little guy" and oppressed people in Europe seemed over time to exclude Jews and non-Europeans. I personally have mixed feelings about movements like Humanism, etc but I can definitely see how the American Negro of the day would have gravitated towards them.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)